Masky is a python library providing an alternative way to remotely dump domain users’ credentials thanks to an ADCS. A command line tool has been built on top of this library in order to easily harvest PFX, NT hashes and TGT on a larger scope.

This tool does not exploit any new vulnerability and does not work by dumping the LSASS process memory. Indeed, it only takes advantage of legitimate Windows and Active Directory features (token impersonation, certificate authentication via kerberos and NT hashes retrieval via PKINIT). The aim of this blog post is to detail the implemented techniques and how Masky works.

Masky source code is largely based on the amazing Certify and Certipy tools. I really thank their authors for the researches regarding offensive exploitation techniques against ADCS (see. Acknowledgments section).

Why another tool?

Redteaming or internal pentesting engagement in Active Directory environments involves the ability to move laterally between systems in order to takeover domain user accounts. There are many ways to compromise domain accounts, increasingly privileged, to eventually become domain administrator. One of the most common strategies is to compromise a system, to elevate its privileges to local administrator and to dump plaintext passwords, NT hashes or TGT from the LSASS process memory. Then, lateral movements via these users’ secrets (PtH, PtT, OPtH, etc.) usually allow to escalate its privileges on the domain by moving from a system to another.

Once a system has been compromised and that you get an acceptable way to execute remote commands, one of the first question you probably think about is “which user am I going to compromise from the LSASS process memory?”. And you are right! Despite all the work perform by system and network administrators to harden the LAN (e.g. by implementing a tier model, by flushing users’ sessions or by applying strong network segmentation on administrative services like WinRM, SMB, WMI, RDP), this attacking methodology is still generally effective.

Other methods to harvest domain credentials, through for instance the DPAPI, could be applied on a compromised system. However, we will not discuss them in this article because they are not directly related to interactive users’ sessions running on each system.

The success of this attacking strategy has been supported by the development of tools allowing, among lots of other features, to dump and parse the LSASS process. The purpose of these tools is to retrieve NT hashes and TGT of domain users’ sessions. Tools such as Mimikatz, that we no longer present, allows to perform this task. For less detection reasons, as well as for more convenience, amazing tools like Lsassy were created to remotely dump the LSASS process via multiple techniques (procdump, nanodump, edrsandblast, etc.) and to parse it locally. This kind of tool also provides to pentester the ability to perform these remote dump through the administrative services that could be exposed by Windows systems, thanks to the impacket python library (e.g. WinRM, SMB, WMI). It basically consists in pushing an executable file, running it via for example the creation of a service or a schedule task and to retrieve the output. Moreover, such tool are now integrated into offensive Active Directory oriented toolbox, like CrackMapExec, which offer orchestration capabilities to easily attack large environments.

However, the dump of the LSASS process memory is not always trivial as it was. Most recent Windows versions now implement security mechanisms such as protected process and Credential Guard. In short words, Protected Process Light (RunAsPPL) restricts the access to the LSASS process to only digitally signed and trusted process. Regarding Credential Guard, this feature basically allows to store the users’ secrets within a separate virtual machine. Additionnaly, companies now rely on the deployment of EDR (Endpoint Detection and Response) or EPP (Endpoint Protection Platform) that can hook Win32API functions allowing to read the memory of a process (OpenProcess, CreateRemoteThread, etc.). These security solutions also scan for known malicious binaries or detect attacker behaviours from usual patterns (static or dynamic analysis).

Although no security solution is foolproof (e.g. kernel land bypasses with signed drivers, RIP PPLDump, SysWhisperer for function hooking, etc.), pentesters may have encoutered difficulties to bypass them from a black box point of view! Therefore, I thought about how to automate other known techniques together in order to avoid harvesting domain users’ secrets only from the LSASS process memory.

The aim of this article is not to describe the LSASS dump functionning, the available countermeasures or to detail how these amazing quoted tools and bypasses works. There are plenty of articles that describe it way better than me!

ADCS for the win

The last years were rich in terms of vulnerabilities helping to takeover a domain. However, I recently had a special focus on the ADCS attack path (Active Directory Certificate Services) thanks to the Certified Pre-Owned paper written by Will Schroeder (@harmj0y) and Lee Christensen (@tifkin_). The differents privilege escalation and persistence techniques based on a PKI implemented via this Microsoft solution offer a really interesting attack surface (e.g. NTLM relay to web enrollement, vulnerable templates exploitation, etc.). In addition to this ressource, I also read the articles written by Oliver Lyak (@Ly4k) on this subject and especially the one regarding the Certifried vulnerability (CVE-2022–26923).

We will not deep dive into how works an ADCS or how its misconfiguration could be exploited. However, it is necessary to understand that such PKI implementation is directly linked to the Active Directory forest where it is deployed and provides, among other features, the ability to authenticate domain users based on certificates.

From all of the information in these articles, two concepts caught my attention:

- A domain user can request a certificate to a CA server by using, for instance, the

User template(implemented by default); - A user certificate can be used to authenticate on the KDC via the PKINIT (kerberos extension).

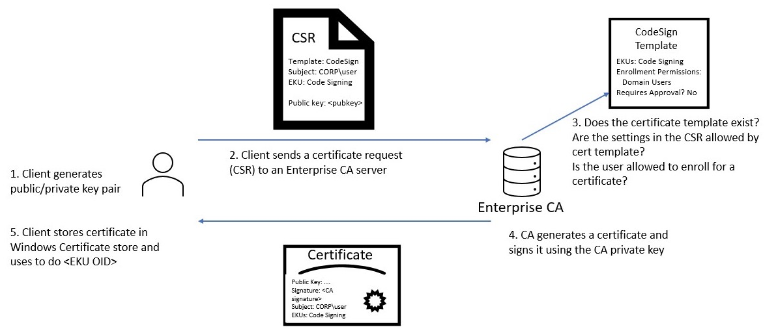

Before we think about exploiting these behaviors, it is important to understand how we can obtain a certificate from the ADCS. First, a domain user can query a CA server to enroll for a certificate, based on a specific template. This enrollement consists in generating a public and private keys in the user’s context. Then, a certificate signing request (CSR), including the public key and the targeted template name, is sent to the CA server. A set of domain checks is performed by the ADCS with the domain controller, based on the requesting domain user. If it succeed, a certificate is generated base on the chosen template. This certificate is finally signed with its CA server private key and returned to the user (PEM format that can be converted in PFX).

This is a very simplified explaination of the ADCS enrollement process. Nevertheless, from an offensive point of view, this mechanism allows an attacker who can execute code in a targeted user context to query a certificate allowing to authenticate on the domain.

Indeed, a certificate queried for example from the User template can be reused to authenticate via the Kerberos procotol. Basically, the user will use the signed certificate to request a TGT from the KDC. The Active Directory can be requested for such authentication thanks to the PKINIT Kerberos extension (Public Key Cryptography for Initial Authentication).

In addition to the obtained TGT, the PKINIT protocol allows to retrieve the NT hash of the requesting user. This technique is identified as THEFT5 within the Certified Pre-Owned paper and was first published on twitter by Benjamin Delpy (@gentilkiwi). This offensive abuse is due to a fallback feature implemented within the PKINIT protocol. From this built-in feature, the NT hash can be retrieved from the obtained TGT (see. UnPAC the hash). The aim of it was to allow the user to authenticate on systems or applications that only support legacy authentication.

If we sum-up a little bit all this information, an attacker able to execute code within its target context can query a certificate to the ADCS and then authenticate on the KDC. Thus, an attacker is able to retrieve a TGT as well as the NT hash in plaintext for each targeted users. Is that not really nice? :)

During pentesting and redteaming engagements, many post exploitation scenarios can be done with the use of these legitimate Microsoft mechanisms.

Imagine that you are local administrator on a server with a running domain administrator session on it. For some reason you cannot dump the LSASS process memory. However, from the RDP session you can hijack its session via, for example, the tscon utility and then request a certificate through the User template. The Certify tool can be used to easily retrieve a valid PEM certificate. Once converted with openssl to a PFX, you can use it with Kekeo, Rubeus or Certipy to authenticate via PKINIT, retrieve a TGT and then the user’s NT hash.

This method relies on legit features and allows to compromise a domain user without touching LSASS on a stealthier way (take care of the Certify binary detection). However, this technique was performed manually via an interactive session through RDP. This remains harder to be automated on a larger scope as the Lsassy / CME tools do by dumping the LSASS process memory through SMB.

After few attempts to develop a tool automating the usage of tscon and Certify via a “ducky script like strategy” (really bad idea btw), I thought about a way to impersonate on a large scale the users’ sessions that were not properly logged off on the remote servers.

The Windows token mechanisms came to my mind and in particular the use of the Incognito tool. Indeed, from an attacker point of view who is local administrator on a system, a privilege escalation could be perform to become NT AUTHORITY/SYSTEM (for instance via a service creation as PSEXEC do). Then, from this privileged access, all running processes on the compromised system can be browsed in order to open the one related to our targeted domain user. Once the process is opened, its associated access tokens can be duplicated and re-used to hijack the user session.

The advantage of this technique is that it automates the process of impersonating users and execute arbitrary code within their context. The following demo shows how it is possible, from a meterpreter session, to easily switch from one user context to another.

McAfee’s security team made a very interesting article about the theft and manipulation of these access tokens. In a nutshell, when a user logs on to a Windows system, a session represented by a Security Identifier (SID) is created. Moreover, an access token is generated by the Local Security Authority (LSA) and is associated with the user’s session. This token is used to describe the security context and privileges of the actual user (groups, etc.). Each process derived from the user’s session inherit of this access token. This allows the system to apply the correct restriction or authorization on the system for a running process (using primary token) or a thread (using impersonation token). Each of these tokens can have different impersonation levels describing the actions that can be performed in the user’s context. The SecurityDelegation is especially useful because it allows to impersonate the user through the network, meaning that ADCS interactions could be performed.

This is once again a topic that would need tons of explaination to be fully covered. But, this mechanism answer to our actual need. Indeed, we are able to fully impersonate domain users’ authenticated on a compromised server, to request a certificate in their context and so to obtain for each of them a TGT and a NT hash.

While writting this article a new release (4.0) of Certipy was made by Ly4k. From lots of new interesting features, the SSPI option was implemented. This allows to use the current user context on a Windows system to take advantage of the other modules without knowing the current user credentials.

Putting it all together

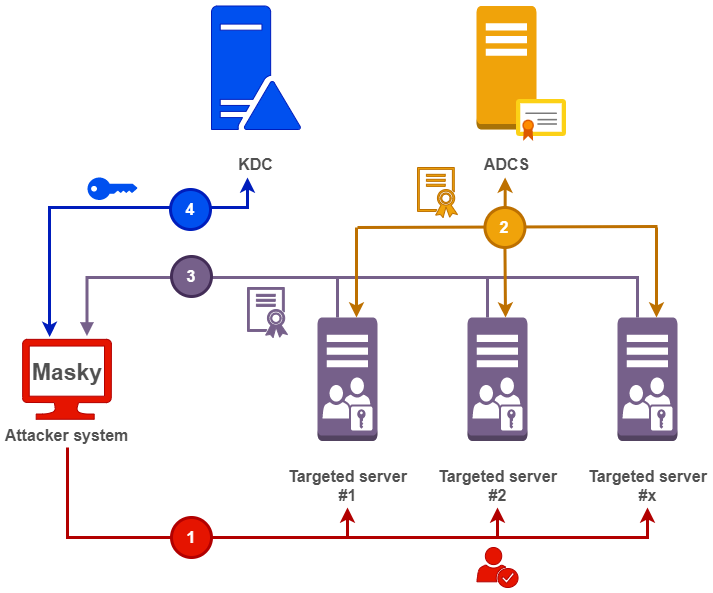

We now have all the elements in our hands! Based on all of these notions, I developed a tool called Masky that automates this process and works like Lsassy does. This tool is composed of a Python part running on the attacker’s system and an executable agent in C# deployed on targeted systems.

The following schema describes the implemented steps for a targeted host.

Step 1 - Deploy and run Masky agent

First, the attacker must own a user with local administrator privileges on the targeted systems. Masky supports plaintext password, NT hashes or Kerberos authentication with a loaded CCACHE file. In case of the exposure of the tcp port 445, an SMB connection is established.

This SMB session allows to push a Masky agent executable into the Windows Temp folder. Once successfuly pushed via the C$ remote share, the ImagePath attribute related to the existing RasAuto service is modified to point on the Masky agent. I chose this method as it is stealthiest to modify an existing service property rather than creating a new one that will be deleted later. This remote code execution method was implemented by Pixis in Lsassy based on the @Cyb3rSn0rlax idea. The RasAuto service was chosen because it is started manually and is deployed by default from older Windows versions to newer ones.

Finally, the modified service is started via the DCERPC Impacket implementation (SCMR) and the Masky agent is launched with NT AUTHORITY/SYSTEM privileges.

Steps 2 and 3 - Query ADCS for certificates

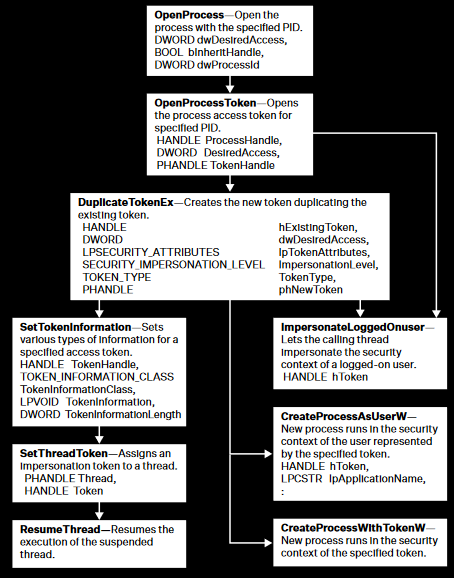

This binary, developed in C#, aims to browse all running processes. For each of them, it performs some checks like what kind of process it is or who is the owner. Then, the process is opened with the OpenProcessToken function to retrieve the associated access tokens. The tokens are duplicated with the DuplicateTokenEx function and finally the current impersonation token of the Masky agent main thread is replaced by the spoofed one with a call to SetThreadToken. These functions are members of the Win32API, their prototypes can be easily retrieved from the Pinvoke website to be used in C#.

For each spoofed user, an asymmetric key pair is generated and a CSR requesting the User template is sent to the CA server. This implementation is entirely based on the Certify tool. The PEM certificate is retrieved and appended within a JSON file with the spoofed username. The Masky agent switch between users by storing its initial access token and restoring it. This avoids to spawn processes or threads to perform this task.

Masky automatically downloads the generated JSON file through SMB as well as a debugging file (in case of a stacktrace). Finally, all files are deleted from the remote server and the RasAuto original ImagePath is restored.

Step 4 - Retrieve users’ secrets from downloaded certificates

The next steps are performed from the local attacker’s system. Indeed, the collected PEM certificates are converted into PFX format and a TGT is requested to the KDC via the PKINIT Kerberos implementation. This TGT is exported in the CCACHE format to be easily loaded on Linux systems (via the command line: export KRB5CCNAME=./file.ccache). Then, a NT hash is retrieved through the PKINIT fallback feature. All of these KDC interactions came from the tools Certipy and PKINITTools (developed by Dirk-jan Mollema). Only minors modifications were made from the original Certipy modules in order to do this job!

This overall process is replicated on each targeted system to store locally the NT hashes, CCACHE and PFX files. All of this allowing to perform further Pass-The-(hash,ticket,certificate) lateral movements! :)

Masky for fun and profit

Masky version 0.0.3 was released besides this article on my github: https://github.com/Z4kSec/Masky.

This version might be “unstable” and special care should be taken while using it to ensure that the RasAuto ImagePath has been correctly restored on the targeted system, in case of an unexpected crash. This should not occured of course, but we never anticipate all behaviors! ;)

Because a demo is sometimes more effective than lots of words, please find below an example of its use.

Note that the FQDN of the CA server and the CA names must be provided to the tool. The User template must also be enabled on it. This information can be easily retrieved with the find Certipy commands as well as via the certutil.exe Microsoft utility.

All parameters and their usage are described within the Masky Github readme. Moreover, the tool can be used as a library to be integrated within other tools.

Below is a simple script using the Masky library to collect secrets of running domain user’s sessions, from a remote target.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

from masky import Masky

from getpass import getpass

def dump_nt_hashes():

# Define the authentication parameters

ca = "srv-01.sec.lab\sec-SRV-01-CA"

dc_ip = "192.168.23.148"

domain = "sec.lab"

user = "askywalker"

password = getpass()

# Create a Masky instance with these credentials

m = Masky(ca=ca, user=user, dc_ip=dc_ip, domain=domain, password=password)

# Set a target and run Masky against it

target = "192.168.23.130"

rslts = m.run(target)

# Check if Masky succesfully hijacked at least a user session

# or if an unexpected error occured

if not rslts:

return False

# Loop on MaskyResult object to display hijacked users and to retreive their NT hashes

print(f"Results from hostname: {rslts.hostname}")

for user in rslts.users:

print(f"\t - {user.domain}\{user.name} - {user.nt_hash}")

return True

if __name__ == "__main__":

dump_nt_hashes()

This generates the following output once executed on my testing lab.

1

2

3

4

5

6

$> python3 ./masky_demo.py

Password:

Results from hostname: SRV-01

- sec\hsolo - 05ff4b2d523bc5c21e195e9851e2b157

- sec\askywalker - 8928e0723012a8471c0084149c4e23b1

- sec\administrator - 4f1c6b554bb79e2ce91e012ffbe6988a

A MaskyResults object containing a list of User objects is returned after a successful execution of Masky.

Please look at the masky\lib\results.py module to check the methods and attributes provided by these two classes.

Detection vectors

From a blueteam perspective, several behaviors can be detected when exploiting such attack path.

First of all, Masky heavily relies on the SMB protocol to execute remote code on the target, but also to deploy the agent and retrieves the results.

Offensive tools relying on this protocol typically interact with three shares: C$, ADMIN$ and IPC$. Wherever the C$ and ADMIN$ shares are mounted as local administrator and are used to push or retrieve files, the IPC$ is related to the usage of named pipes exposed by the remote system. It basically allows to interact with the features exposed on the target through legitimate protocols. Indeed, the DCERPC protocol allows, as it names suggest, to call remote procedures allowing for example to create services (via \pipe\svcctl) or scheduled tasks (via \pipe\atsvc). I strongly recommend diving into Impacket source code and especially their example scripts to understand how it works (smbexec.py, atexec.py, etc.).

From this information, the following Windows event log IDs can be collected on your SIEM to create detection rules for such remote code execution over SMB:

4698: A schedule task was created;4699: A schedule task was deleted;4702: A schedule task was updated;7045: A new service was created;5145: A network share object (file or folder) was accessed.

The use of service or schedule tasks in a short period of time (e.g. creation, modification or deletion) could be an interesting weak signal to correlate with administrative shares interactions (C$ / ADMIN$), as well as the IPC$ special share. Indeed, this could be a sign of the use of such lateral movement techniques. False positives can occur based on these rules depending on the administration tools used through the corporate LAN (e.g. PSEXEC). To go deeper in such detection, rules can be combined to identify the spawning of suspicious lolbins, unsigned binaries or commonly executed recognition commands (e.g. whoami, net user, etc.) from the process tree of the schtasks.exe (schedule tasks) or winexesvc.exe (services) processes.

Once the lateral movement detection is monitored, the behaviors related to the locally deployed agent has to be handled.

The token impersonation part may be difficult to be detected due to the usage of legitimate built-in Microsoft Win32API functions. The McAfee’s article includes a diagram that sum-up the call of such functions during a token impersonation attempts.

In Masky case, the OpenProcessToken, DuplicateTokenEx and SetThreadToken are primarily used to perform session hijacking on active users. A Yara rule dedicated to the detection of malwares relying on such Win32API functions was written within the quoted McAfee article and could be a good start. Note that this detection method is more related to static analaysis during incident response. Without an in-depth manual analysis, such automated detection could be bypassed by an attacker applying techniques such as obfuscation, packing, process hollowing with dynamic unxor of the payload, etc.

In addition, the interaction with the ADCS instance could be an interesting way to detect Masky execution. The Certified Pre-Owned article describes detection and preventive actions that could be applied on ADCS environment. From the listed detection methods, the one referenced DETECT1 recommends to monitor the users’ certificates enrollement via the Event ID 4886 (“Certificate Services received a certificate request”) and their approval via the Event ID 4887 (“Certificate Services approved a certificate request and issued a certificate”). However, depending on the environment, the monitoring of all certificate requests could not be efficient when there is a large number of legitimate requests.

A second method that could generate less false positive detection is suggested by the Specterops team. Referenced DETECT2, this detection method is based on the identification of Kerberos authentication made via a certificate, through PKINIT. Indeed, the Event ID 4768 (“A kerberos authentication ticket (TGT) was requested”) is generated on the KDC server. When a TGT is queried with a certificate, this event log contains 3 new fields in the Certificate Information section (Issuer, Serial Number and Thumbprint). Modern environments less use this protocol, and could therefore allow to detect malicious authentication attempts with a previously obtained certificate.

Finally, in case of a widespread Masky usage, the deployed agent may be automatically detected via a static analysis by common EPP or EDR if used as part of the PyPi package (embedded agent executable).

What’s next?

First, an optimization of the token impersonation harvesting within the Masky Agent has to be done. Then, lots of debugging may be performed regarding unexpected bugs based on other environments than my lab.

The published version actually includes minimal functionnalties to be used in pentesting engagements.

However, I planned to implement the following features:

- Ability to dynamically change the modified service (default

RasAuto); - Option to automatically retrieve the CA server and look for the User template;

- Add multiple execution methods through SMB (schedule task, WMI, creation of service, etc.);

- Deploy the Masky agent as a XORed payload (with a random key) and dynamically load it through a

svchost.exelaunched process (process hollowing technique).

A CrackMapExec module could also be developed if Masky has some interest for the info sec community :)

Acknowledgements

- Olivier Lyak for the Certipy tool and the associated articles

- Will Schroeder and Lee Christensen for the Certify tool and the Certified Pre-Owned article

- Dirk-jan for the PKINITtools and its ADCS NTLM relay article

- SecureAuthCorp and the associated contributors for the Impacket library

- Pixis for the tool Lsassy

- Incognito tool and its Metasploit implementation

- S3cur3Th1sSh1t for the tool SharpImpersonation and the associated article

- McAfee for their article regarding the token impersonation techniques