A Bit of Context

IoctlHunter is a command-line tool designed to simplify the analysis of IOCTL calls made by userland software targeting Windows drivers.

TL;DR: Here are the videos demonstrating the usage of IoctlHunter

From a cybersecurity perspective, IoctlHunter empowers security researchers to identify IOCTL calls that could potentially be reused in standalone binaries to perform various actions, such as privilege escalation (EoP) or killing Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR) processes.

This technique, also known as BYOVD (Bring Your Own Vulnerable Driver), involves embedding a signed vulnerable driver within a binary. Once deployed on a targeted system, the binary loads the driver and sends IOCTL calls to it to execute specific offensive actions with kernel-level privileges.

This article was written in continuity of a blog post written by Alice. In this awesome article, Alice explains how it is possible to perform a static analysis of Windows drivers to retrieve features allowing a userland software to kill protected processes such as EDR ones.

While reading it, it definitely challenged me to build a tool that enables lazy reverse engineers to easily discover drivers providing juicy features for offensive use cases.

We will not deep dive into how drivers work or describe all their interactions with userland processes in detail. Thus, I strongly recommend reading Alice’s blog post to gain a deep understanding of how drivers work and how to exploit them.

However, before understanding how IoctlHunter works, let me introduce a few key concepts.

Driver Loading

First, drivers must be loaded on the running Windows system. This can be achieved by running the following command lines:

1

2

$> sc.exe create MyDriver binPath= C:\windows\temp\MyDriver.sys type= kernel

$> sc.exe start MyDriver

As you can see, the load of a driver consist in starting a service. Thus, the same result can be achieved by performing the following steps:

- Create a registry path within

HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Services\MyDriver(see. the function RegCreateKeyExW fromAdvapi32.dll) - Set multiple registry key within it including the

ImagePathwhich is a string pointing to the absolute file path where the driver binary is stored on the disk (see. the function RegSetValueExA fromAdvapi32.dll) - Start the service and load the driver by specifying the newly created registry path (see. the function NtLoadDriver from

ntdll.dll)

Once your driver successfully loaded, you will need to open a handle on it to interact with it. This can be achieved by calling function such as CreateFileA

The tool Backstab, developed in C++ by Yasser, provide a very nice implementation of arbitrary driver loading and unloading there: Driverloading.c

Run kernel land code

Once you obtain a handle on your loaded driver, you are now able to send instruction to it. Indeed, drivers can exposed specific functions to be run on the kernel side.

In order to specify which function must be executed, userland programs can send the IOCTL (I/O control code). This 32 bits value is bascically dedicated to indicate to the driver which function must be called by within the drivers code.

The DeviceIoControl function (see. MS documentation) provides this interface between user land programs and the driver code running in the kernel side.

Few parameters are required to do the stuff:

- A handle to the targeted driver (

hDevice) - The transmitted IOCTL code (

dwIoControlCode) - The associated transmitted data (

lpInBuffer) and its size (nInBufferSize) - The returned data (

lpOutBuffer,nOutBufferSize)

Some examples of interesting IOCTL calls involve transmitting basic data in the lpInBuffer parameter, such as an integer specifying a process to be terminated. However, the typical usage of DeviceIoControl often requires submitting a custom C-like structure in this parameter, containing various data types. Understanding how to construct such a structure may necessitate static analysis of the driver.

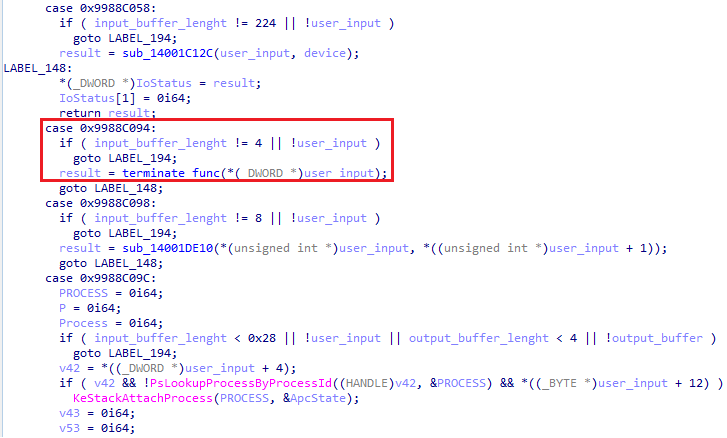

In such case, a good approach is first to identify the IOCTl code related to the function that we are intersting in. Then, with a reverse software like cutter, ghidra or IDA, we can start by looking for the Driver main function and browse the code until we found “a switch case” pattern were the dispatching between all IOCTL codes is made between all driver implemented functions (not always the case!).

Finally, once a static comparison between our IOCTL code is made, we are not that far of the paramater containing the lpInBuffer pointer. If you look for data pointed by it, you should be able to analyse the provided structure.

Chain it

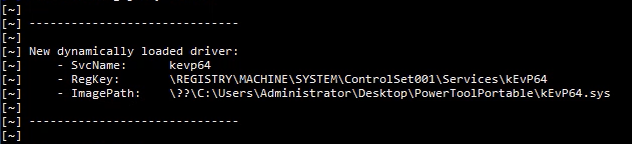

As we’ve discussed, multiple calls can be intercepted to dynamically retrieve drivers loaded by a program based on changes to registry keys.

Moreover, DeviceIoControl calls contain sufficient information to help us retrieve the portion of driver code that will be executed, the data sent as parameters to perform tasks, and the size of this data.

In short, from a “user land” perspective, a security researcher can intercept all the previously mentioned Win32 functions to dynamically obtain the following information:

- Automatically detect loaded drivers.

- Intercept IOCTL calls and the associated data.

- Retrieve the driver using the handle passed as a parameter to

DeviceIoControl.

With this information, you can extract necessary data in a lab while analyzing a tool with a driver capable of executing kernel-level actions for offensive purposes.

Once you’ve gathered all this information by intercepting these functions or by statically reversing the driver, you’ll have everything needed to create a binary that loads the driver and sends the correct IOCTL with the appropriate data.

However, in real world scenarios, multiple drivers can be dynamically loaded and called by a single executable. This can make it challenging, with the hooking approach, to identify the IOCTLs that match the observed features while using tools not specifically designed for this purpose. That’s why I began developing IoctlHunter.

Ease the process with IoctlHunter

Unlike some of today’s tools, IoctlHunter differs from static driver analysis approaches. The tool aim is to execute a binary that is likely reliant on drivers providing interesting offensive features. By exploring the various options presented by such programs, IoctlHunter helps in monitoring the IOCTL calls that occured.

The mindset to adopt when using IoctlHunter is a bit like using BurpSuite to analyze a website. You navigate to the options that might interest you and look in IoctlHunter for the potential associated IOCTL.

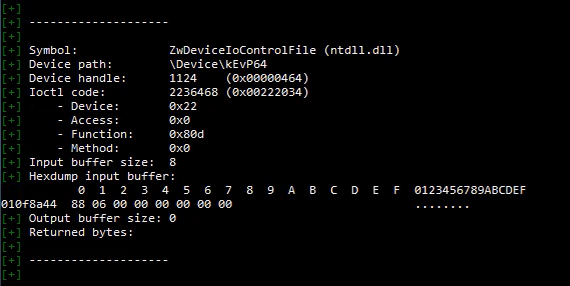

The tool provides several essential pieces of information to replay an IOCTL, thanks to the DeviceIoControl function (see MS documentation):

- The target driver

- The transmitted IOCTL code (

dwIoControlCode) - The associated transmitted data (

lpInBuffer) and its size (nInBufferSize) - The returned data (

lpOutBuffer,nOutBufferSize)

With this information, it is possible to conduct a static analysis of the driver to scrutinize the associated code in detail, starting from the IOCTL code. However, it is also possible to directly replay this IOCTL call if its usage appears straightforward.

Successful use of IoctlHunter empowers Red Teamers and Penetration Testers to create a standalone executable that installs a specific driver and issues one or more IOCTL calls to perform various tasks. The advantage lies in the ability to execute signed drivers with kernel privileges, and to exploit useful features in an offensive way.

Obviously such standalone BYOVD binaries requires the SeLoadDriverPrivilege flags to be able to do the magic!

How it works?

As IoctlHunter base its analysis on hooking, I decided to use the most advanced and easily scriptable tool to do this job: Frida. Frida is basically a dynamic instrumentation tool which support Python to script with. Its main usage consists in injecting code into a process and to hook functions within running processes, facilitating a debugging, as well as reverse engineering. I am sure lots of you already used it for mobile pentests (certificate pinning bypass FTW!) or to easily reverse thick clients.

From this awesome libraries, IoctlHunter is able to spawn or attach to an existing process to be analyse. Then, a RPC communication is established between the two process and IoctlHunter is able to hook useful functions in order to collect all IOCTL calls, apply fynamic filters on them and much more!

The full developped Frida script can be found there: script.ts

Demo with PowerTools

In Alice’s blog post, titled “Finding and Exploiting Process Killer Drivers with LOL for $3000,” she demonstrated how a static reverse engineering analysis of the kEvP64.sys driver used by the PowerTool software allowed her to develop a process killer tool that could terminate protected processes with kernel-level privileges.

The following video demonstrates how IoctlHunter makes it easy to identify all the elements needed to terminate protected processes using the same tool:

Subsequently, using the information obtained, a Golang package provided in the IoctlHunter repository allows you to load and replay the IOCTL calls:

Limitiations

It is important to underline that IoctlHunter is not designed to supplant traditional static or dynamic reverse engineering methods used for vulnerability discovery in drivers. Instead, it serves as a complementary tool to help in the dynamic identification of specific IOCTL calls information, providing additional insights into the behavior of drivers loaded by a given software. As describe in this article, the complexity resides in the identification of the data structure linked to the lpInBuffer data buffer.

Furthermore, the tool primarily involves injecting itself into processes for analysis. However, this approach may not work directly when targeting processes are protected with anti-tampering mechanisms. For instance, EDR (Endpoint Detection and Response) processes may not allow injection via Frida without the prior use of a specific driver to open a handle on these protected processes.

IoctlHunter is designed to gather IOCTL data in a controlled lab environment. This enables the disabling of security mechanisms and the utilization of existing techniques to inject into protected processes.

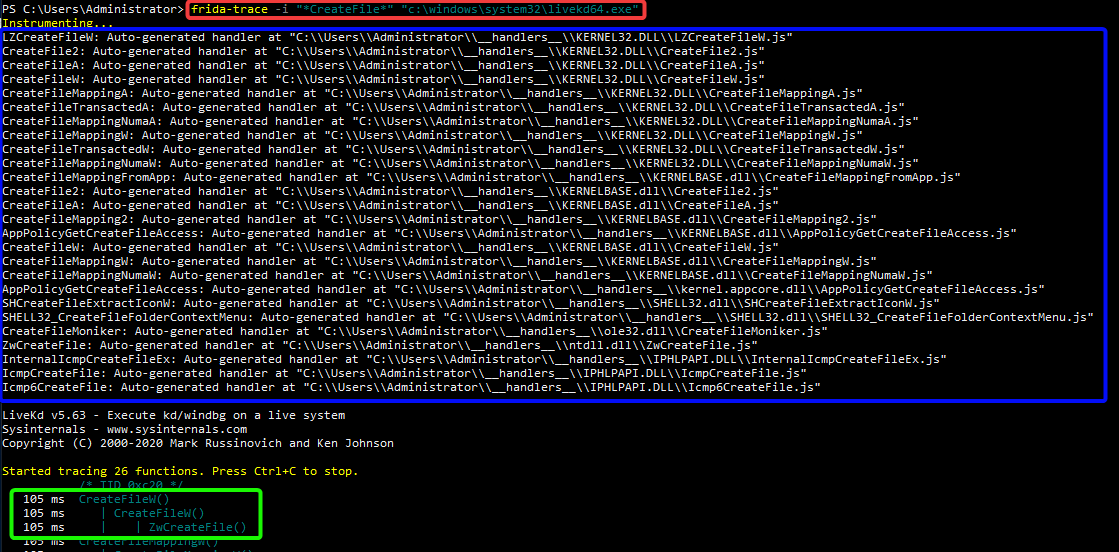

Finally, the actual version of IoctlHunter allows for hooking various functions within the Windows API that have multiple implementations and/or function prototypes (see blue box on the screenshot below). This diversity arises from the existence of functions suffixed with either ‘W’ or ‘A’, with ‘W’ denoting wide-character (Unicode) and ‘A’ for ANSI character functions, depending on the string encoding used. Additionally, some functions may have ‘Ex’ suffixed, which generally indicates an extended version of the function with additional features or parameters.

Furthermore, certain functions may be prefixed with ‘Nt’ or ‘Zw’, signifying native API calls that interact more directly with the operating system’s kernel. However, these functions ultimately call each other, and not every program necessarily calls the same function (see green box on the screenshot below). IoctlHunter is designed to hook the most common functions by default to avoid duplication. In cases where it’s necessary, the --all-symbols option allows for hooking all ‘versions’ of a function but may result in duplicate function calls.

What’s next?

First, it could be interesting to facilitate the ability to replay IOCTL calls. When the --output parameter is enabled, the generated file contains a base64 encoded buffer in the data provided through the lpInBuffer parameter of the DeviceIoControl function. It might be cool to introduce a feature that allows the replay of such IOCTL calls on the same driver for debugging purposes.

The second point of improvement is not directly related to IoctlHunter. Instead, it concerns the project Loldrivers.io created this year by The Haag, which provides an extensive database of known vulnerable drivers. This database serves as an excellent starting point for identifying IOCTL vulnerabilities in BYOVD (Bring Your Own Vulnerable Driver) attacks (see Alice’s tool LOLDrivers_finder).

However, the Loldrivers project does not offer detailed information regarding specific vulnerable features or how to exploit them (IOCTL codes, required input data, etc.). Obviously, the collection of this information typically involves significant reverse engineering work. Still, it might be beneficial to reference such details when available, similar to how it’s done for PowerTools, ProcExp512, RTCore64, and other vulnerable drivers. This could assist in the development of tools for drivers already known to be vulnerable (and potentially blacklisted by Microsoft). Additionally, it might contribute to the creation of more precise detection rules based on EDR telemetry (not tested!)